The Spanish word catrín is often translated as “dandy” – an elegant, well-dressed man. That, of course, makes a catrina his female equivalent.

Thanks to the nineteenth century Mexican illustrator, Jose Guadalupe Posada (along with a little help from muralist Diego Rivera), the word Catrina – with a capital C – has come to signify one of those iconic skeleton ladies that typical of Día de los Muertos celebrations.

You’ve seen them before. And, if you hadn’t seen them before last month, thanks to the hit Disney/Pixar movie Coco, you’ve almost certainly seen them by now. They’re long and lean (they’re comprised only of bones, after all – although somehow many manage to have breasts), and they’re generally dressed in elaborate evening gowns accented by feather boas or other forms of neck adornment – like snakes.

Catrinas almost always wear glamorous hats with enormous brims, and it’s not uncommon for them to be seen smoking cigarettes or holding fancy purses.

While a Catrina can be depicted on a mural, in a painting, or even on film, the Catrinas in Capula, Mexico are all made from clay. They are statues, ranging in size from a few inches tall to near-life-size ladies ready to welcome guests in your entryway. Capula, a village of about 5000 people outside of Morelia, is the self-proclaimed Catrina capital of the world. This is no accident. To explain why, a little history is helpful.

Jose Guadalupe Posada was a Mexican printmaker and graphic artist who produced advertisements, posters, and, most significantly, political cartoons from about 1870 until the time of his death in 1913. His satirical work targeted the country’s “new rich” and its notoriously corrupt figures, including President Porfirio Diaz. This segment of Mexican society emulated the customs and dress of Europeans and generally played down or denied any indigenous heritage they might have had.

Posada used skeletons dressed in European clothing to represent the Mexican bourgeois class and call attention to what he perceived as their hollow lifestyles and moral codes. He was regularly published in newspapers with huge circulation numbers.

His work might have been forgotten were it not for Diego Rivera’s inclusion of a Posada-esque skeleton lady in his well-known 1946 mural, Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en La Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon along the Central Alameda). Rivera depicted both himself and Posada in this mural (along with Rivera’s wife Frida Kahlo), and he placed his skeleton lady, who he called “La Catrina” between the two men.

His Catrina was even more ornate than Posada’s original, and she represented both the Mexican ability to live with and celebrate death and death’s democratic leveling of the class system.

Fast forward to 1980. Another Mexican artist, Juan Torres, unable to afford the rents in Morelia, moved out to the rural village of Capula. There he worked on his paintings and sculptures, but he also hatched an idea that would foster economic growth in the town.

Since pre-Columbian times, Capula had been a pottery production center. Clay was sourced nearby, and the local production and painting traditions had endured for generations.

Torres thought that Capula would be an ideal place for crafting Catrinas. The residents knew how to work with clay and they knew how to paint. He opened up a workshop and began training them in how to adapt these skills to making Catrinas. These students have gone on to train others, and today, there are over sixty families in Capula making Catrinas.

At first, Catrinas were sold primarily in the existing artisan markets and in Torres’ workshop. Gradually, as they gained popularity and began to be exhibited in the US, more and more shops selling Catrinas opened along the town’s main street. Today, that street is lined with about thirty shops, most of which are selling at least a handful of Catrinas.

In 2011, Capula held its first annual Catrina Festival. Last year’s attendance was reported to be around 5000 people, and it included a juried Catrina competition. (click here for a YouTube video of the 2015 fest) The timing of the festival coincides with the annual Día de los Muertos celebrations all around the Mexican state of Michoacán – a two-week period in late October and early November when the area comes alive.

I visited Torres’ workshop two months after the festival and saw only five or six Catrinas in the shop. They’d completely sold out during festival week, the shopkeeper said, and had yet to catch up on their backlog of work.

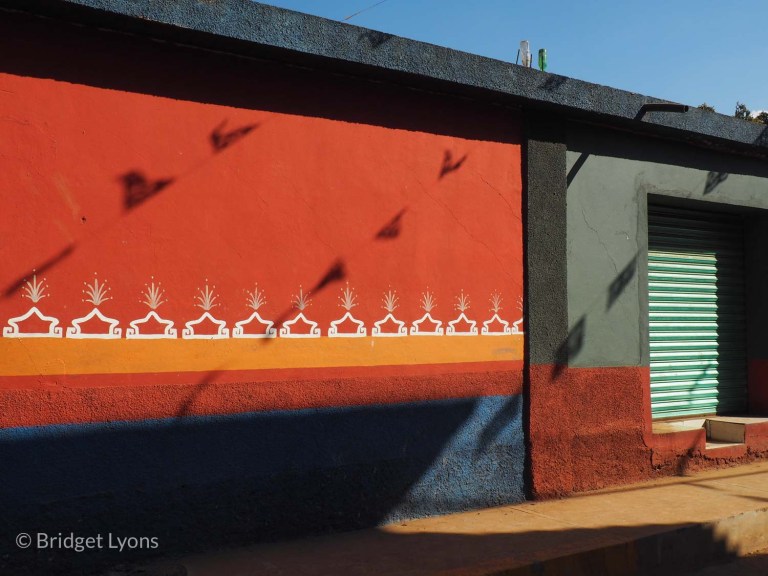

Capula had been described as a dusty, non-descript town on a number of websites I consulted. That is clearly changing. Since the advent of the festival and the popularity of the village’s Catrinas, the locals have begun to paint their walls with patterns similar to those used on their pottery.

They’ve also taken to painting Catrina portraits outside the shops and even decorating the areas around gas meters.

There are flags flying throughout town, and last week, the street was being torn up to allow for the burial of telephone and electrical cables. The place is will no doubt be transformed by the time next year’s Catrina festival rolls around.

I’ve got it on my calendar.

Vamanos! Y tambien a las alfombras en Guate, y, y, y…..loved this….

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading, Carolyn! The locals told me Dia de los Muertos in the Pátzcuaro vicinity is a lot like Dinsneyland, but still….

LikeLike

the pottery is GORGEOUS. Thanks for sharing your story about the town and the artwork.

LikeLike

Dang, if I’d known you’d like it so much, I would have bought you a piece! (I can’t buy anything for myself while on the storage-unit-life-train…) – thanks for reading, chica!

LikeLike

“y, y, y, y, ” You tambien I want to go there, too. I wish you could have brought me a life-size clay Catrina in your suitcase. LOL No! seriously, be our guide to Capula next year. Maybe just a few days prior to Dia de los Muertos so we do not have to complete for space with so many incarnated souls. I am Mexican and a traveler and your stories feed my soul. Thank you for such thoughtful writ!

LikeLike

Gracias por leer, Elva! Si, una Catrina gigantesca seria pefecta en tu recibidor. Un dia tengo que conducir alla para recoger unas Catrinas y unos muebles! I would LOVE to experience your homeland with you!!

LikeLike